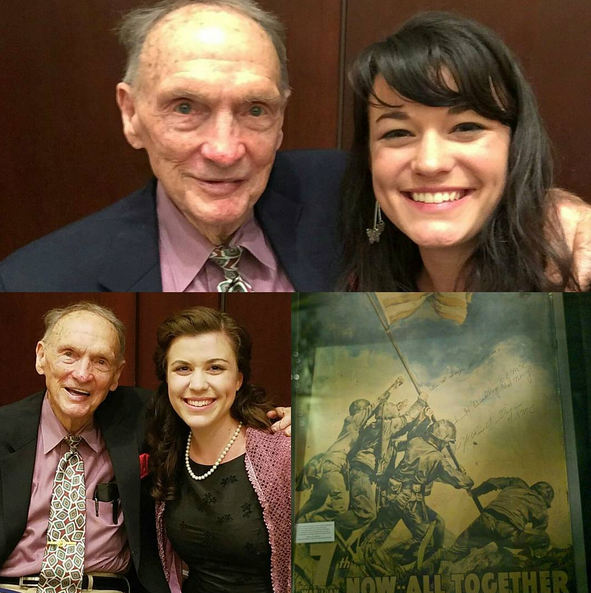

Dinner with Fred

/Yesterday, Jubilee and I were invited to attend a special dinner put on by the Nimitz Foundation with our dear friend and Iwo Jima veteran, Fred Harvey. Mr. Harvey's stories from Iwo are among the most descriptive and remarkable that I have ever heard, and when hearing them, there is no doubt as to his bravery.

On February 20th "His three man patrol (which was sent out to establish contact with the adjoining company) was ambushed by heavy fire from an enemy machine gun and one of the men was seriously wounded." Mr. Harvey, "dragged the fallen Marine under heavy fire to the shelter of a nearby hole. Remaining with the wounded man while his companion went for aid, he held off the hostile forces with his rifle and hand grenades until the arrival of the rescue party." (The next morning) "Then, exposing himself to enemy fire and directing accurate heavy fire on the Japanese position, he successfully covered the evacuation of the casualty." He received the Silver Star for this remarkable and courageous event.

About the 7th day of action, he took 3 grenades which gave him a purple heart and put him out of action for the rest of the war. His stories of the post-war are almost as wild as when he was in the Corps, and never ceases to leave all listeners on the edge of their seats and nearly choking with laughter.